Building Websites With Hugo

published: January 25, 2025

tags:

static-websites |

hugo |

personal-site |

reading time: 32 minutes

These notes were written based on learnings from the book Build Websites using Hugo by Brian P. Hogan which was listed on the External Learning Resources page on the official Hugo website.

Why this book?

I first learned how to create a static site using Hugo through the official documentation. It’s an excellent starting point, and if you’re a web developer, you can have a site up and running in just an afternoon.

However, setting up a theme as a novice can be challenging. Not all theme creators provide documentation as detailed or beginner-friendly as Hugo’s. Many assume you already have some experience with Hugo, so I had to figure out certain configurations through trial and error. Surprisingly, I really enjoyed this process—I thrive on the “just hack at it” mindset.

But why a book?

I wanted to migrate my existing static site, built with vanilla HTML, CSS, and JavaScript, to Hugo so I could easily publish blog posts and notes like this one. Developing my own theme was important to me because I wanted the site to feel truly personal. Since I learned to code at university, I’ve always preferred books over YouTube for diving deep into a topic. So, I decided to grab a book and get to work.

I perused the External Learning Resources on the Hugo website and chose Brian P. Hogan’s book because its approach felt more aligned with what I was setting out to do:

In this book, you’ll use Hugo to build a personal portfolio site that you can use to showcase your skills and thoughts to the world

Preface

Are you using a database to serve content that rarely changes? Like WordPress or Ghost. However, since most content doesn’t change in real time, you’re sacrificing speed and scalability for features that benefit content creators and developers instead of the people who want to read your content. And that additional complexity means you need more resources in production too: more servers to handle the traffic, standby database servers, a caching layer you have to manage, and more.

There’s no better way to make a snappy content site than by serving static pages from a traditional web server or a content delivery network (CDN). But you don’t have to give up the rapid development features you’ve come to expect. Static site generators, like Hugo, give you a fantastic middle ground. You get the theming and content management features of a database-driven site without the bloat, security vulnerabilities, or complexities associated with caching.

Chapter 1: Kicking the Tires

Installation

Start by installing Git, Go, and Dart Sass as they are commonly used when working with Hugo.

Ubuntu

Following the instructions from the Hugo Installation page you can install Hugo’s single binary by using the following command:

sudo apt install hugo

And then to check the installation, check the version by using the following command:

hugo version

The hugo command has several subcommands that you’ll use as you build your site. You can see a list of all commands with hugo help.

Windows

Follow the instruction from the Hugo website.

For Go see the Download and install section of the Go website.

Then to install Hugo from CMD run:

winget install Hugo.Hugo.Extended

Mac

Follow the instructions from the Hugo website:

brew install hugo

Creating Your Site

Hugo has a built-in command that generates a website project for you; this includes all of the files and directories you need to get started.

Execute the following command to tell Hugo to create a new site named portfolio:

hugo new site portfolio

The expected output:

Congratulations! Your new Hugo site was created in /home/ibrahim/Software Development/Repositories/personal-platform/2025/hugo/portfolio.

Just a few more steps...

1. Change the current directory to /home/ibrahim/Software Development/Repositories/personal-platform/2025/hugo/portfolio.

2. Create or install a theme:

- Create a new theme with the command "hugo new theme <THEMENAME>"

- Or, install a theme from https://themes.gohugo.io/

3. Edit hugo.toml, setting the "theme" property to the theme name.

4. Create new content with the command "hugo new content <SECTIONNAME>/<FILENAME>.<FORMAT>".

5. Start the embedded web server with the command "hugo server --buildDrafts".

See documentation at https://gohugo.io/.

The following will be created:

archetypes: where you place Markdown templates for various types of content. An “archetype” is an original model or pattern that you use as the basis for other things of the same type. Hugo uses the files in the archetypes folder as models when it generates new content pages. There’s a default one that places a title and date in the file and sets the draft status to true.hugo.toml: holds configuration variables for your site that Hugo uses internally when constructing your pages, but you can also use values from this file in your themes.content: holds all of the content for your site. You can organise your content in subdirectories like posts, projects, and videos. Each directory would then contain a collection of Markdown or HTML documents.data: holds data files in YAML, JSON, or TOML. You can load these data files and extract their data to populate lists or other aspects of your site.layouts: folder is where you define your site’s look and feel.static: holds your CSS, JavaScript files, images, and any other assets that aren’t generated by Hugo.- The

themesdirectory holds any themes you download or create. You can use the layouts folder to override or extend a theme you’ve downloaded.

Step 1: Configuration

Change the hugo.toml configuration according to your information.

baseURL = 'https://ibrathesheriff.com/'

languageCode = 'en-gb'

title = 'The Sheriff's Portfolio'

Here we change ’en-us’ to ’en-gb’ as I intend to use United Kingdom English. See ISO language codes.

Step 2: Building the home page

In a Hugo site, you define layouts that contain this skeleton, so you can keep this boilerplate code in a central location. Your content pages contain only the content, and Hugo applies a layout based on the type of content.

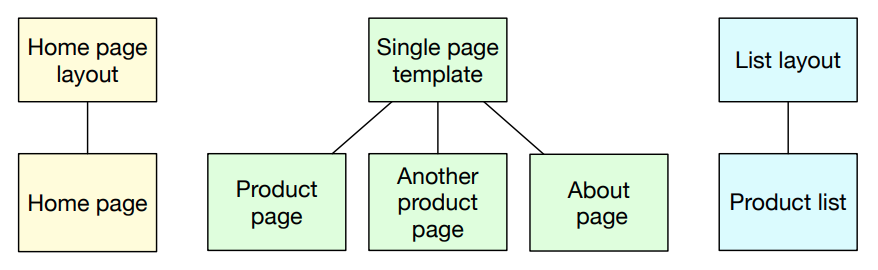

Hugo needs a layout for the home page of your site, a layout for other content pages, and a layout that shows a list of pages, like an archive index or a product list. The following figure illustrates this relationship:

As you can see in the figure, the “home page” of the site has its own layout. The “Product list” page has a “list layout” associated with it. However, the two product pages and the “About” page all share a layout.

Let’s start with the home page layout. Hugo uses a separate layout for the home page because it assumes you’ll want your home page to have a different look than other content pages.

Create the file layouts/index.html and add the following code, which defines an HTML skeleton for the home page:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en-US">

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title>{{ .Site.Title }}</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>{{ .Site.Title}}</h1>

{{ .Content }}

</body>

</html>

To pull in data and content, Hugo uses Go’s http/templates library in its layouts. It’s worth exploring when you want to build more complex templates.

In addition to the HTML code, there are some spots between double curly braces. This is how you define where content goes, and the content can come from many places. The {{ .Site.Title }} lines pull the title field out of the hugo.toml file you just edited and place it into the <title> and <h1> tags. The .Site prefix tells Hugo to get the value from the site’s data rather than from the page’s data.

The {{ .Content }} line displays the content for the page, which will come from an associated Markdown document in your site’s content folder. Note that this doesn’t use the .Site prefix, because this data is related to the page. When

you’re working with a Hugo layout, there’s a “scope”, or “context” that contains the data you want to access. The current context in a template is represented by the dot.

We now need to create the _index.md file in the content directory. This is where the {{ .Content }} will come from.

Then add some data/content to the _index.md file:

This is my portfolio.

On this site, you'll find

* My biography

* My projects

* My résumé

Hugo has a built-in development server that you can use to preview your site while you build it. Run the following command to start the server:

hugo server

Hugo builds your site and displays the following output in your console letting you know that the server is running:

...

Web Server is available at http://localhost:1313/ (bind address 127.0.0.1)

Press Ctrl+C to stop

Hugo’s development server automatically reloads files when they change

Step 3: Creating a page using Hugo’s content generator i.e. Creating Content Using Archetypes

When you created content/_index.md, you created the file manually. You can tell Hugo to create content pages that contain placeholder content. This way, you never have to start with a blank slate when creating content. Hugo uses archetypes to define this default content.

In this the current archetypes/default.md will provide the initial structure:

title: "{{ replace .Name "-" " " | title }}"

date: {{ .Date }}

draft: true

This is a Markdown file with YAML front matter and a little bit of templating code that will generate the title from the filename you specify, and fill in the date the file is generated. Hugo uses the front matter of each file when it generates pages.

Note if the draft field is set as true then the page will be skipped when generating the site pages.

The hugo new command uses this file as a template to create a new Markdown file. Try it out. Create a new “About” page with this command:

hugo new about.md

This created a about.md file in the content directory containing the following:

+++

date = '2025-01-21T18:51:40+02:00'

draft = true

title = 'About'

+++

Now let’s create a layout for the page. Remember that the layout you created, index.html, is only for the home page of the site. The “About” page you just created is an example of what Hugo calls a “single” page. As such, you need a “single page” layout to display it.

You can create different single page layouts for each content type. These get stored in subdirectories of the layouts directory. To create a default single page layout that every content page will use, store it in the layouts/_default directory.

Now we can create the single page layout file - layouts/_default/single.html using the index.html and add the following line to display a title for the page:

<h2>{{ .Title }}</h2>

The site title, page title, and page content are all visible. The page title comes from the about.md file’s front matter, while the site title comes from the hugo.toml file.

Hugo doesn’t clean up the public folder. If you were to remove some pages or rename them, you would need to delete the generated versions from the public folder as well. It’s much easier to delete the entire public folder whenever you generate the site:

rm -r public && hugo

Alternatively, use Hugo’s --cleanDestinationDir argument:

hugo --cleanDestinationDir

You can tell Hugo to minify the files it generates. This process removes whitespace characters, resulting in smaller file sizes that will make the site download faster for your visitors. To do this, use the --minify option:

hugo --cleanDestinationDir --minify

Chapter 2: Building a Basic Theme

So far, you’ve placed all of your layout files into your Hugo site’s layouts directory, but Hugo has another mechanism for controlling how things look: themes. This will reduce duplicate code and make it more manageable to maintain the project.

A basic Hugo theme only needs these files: layouts

|-------default

|---- list.html

|---- single.html

|-------index.html

Generating the Theme

You can make a theme by creating a new directory in the themes folder of your site, but Hugo has a built-in theme generator that creates everything you need for your theme. Execute this command from the root of your Hugo site to generate a new theme named basic:

hugo new theme basic

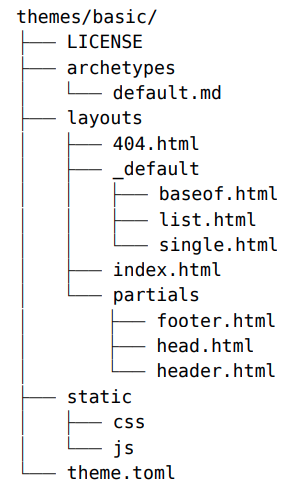

This command creates the themes/basic directory and several subdirectories and files:

Before you can use the theme you have to tell Hugo about it by adding a line to your site’s configuration:

baseURL = "http://example.org/"

languageCode = "en-us"

title = "Brian's Portfolio"

theme = "basic"

The theme has a place for its own archetypes, as well as directories to store the layout files and static assets like stylesheets, scripts, and images. Each theme has a license file so you can open source your theme if you choose, as well as a configuration file where you can store theme-specific configuration values.

Using Content Blocks and Partials

Your home page layout and single page layout both contain the HTML skeleton. That skeleton is going to get a lot more complex once you add a header, footer, and navigation. Instead of duplicating that code in multiple places, Hugo provides a single place for you to put your skeleton so that all other layouts can build on it.

themes/basic/layouts/_default/baseof.html - This file will be the “base” of every other layout you’ll create, hence its name. And instead of including the full skeleton, it’s pulling in other files, or partials, which contain pieces of the layout. Placing common pieces in partials makes it easier for you to reuse these across different layouts, and it helps you think about parts of your site as components.

You will see the partials placed like so:

{{- partial "head.html" . -}}

Previously, when you’ve used those curly braces to inject the title, you used {{. But this code uses {{-. The dash suppresses whitespace characters in the output, such as spaces and newline characters. Placing a dash after the opening braces removes all whitespace in front of the expression, and placing the dash in front of the closing braces removes whitespace after the expression.

In addition to the dashes, there’s a dot after the name of the partial. The partial function takes a filename and a context for the data. In order to access data like the page title and content, you have to pass the context to the partial function, and a period means “the current context.” Remember that the default context for a layout is the Page context, so when you pass the dot to the partial function, you’re making the Page context available to the partial.

The template generator also created these files, but it left them blank. Let’s fill them in, one piece at a time.

Step 1: Fill in the head

The first partial listed in the baseof.html file is the head.html file, which you’ll find in themes/basic/layouts/partials/head.html. This file will contain the code that would normally appear in the head section of a website. Open it in your editor.

Add the following:

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1">

<title>{{ .Site.Title }}</title>

</head>

Step 2: Fill in the header

The next partial reference is the header.html file, so open the file themes/basic/layouts/partials/header.html. This file will hold the header of your page. It’s where you’ll put the banner and navigation:

<header>

<h1>{{ .Site.Title }}</h1>

</header>

<nav>

<a href="/">Home</a>

<a href="/about">About</a>

<a href="/resume">Résumé</a>

<a href="/contact">Contact</a>

</nav>

Step 3: Fill in the footer

Finally, create the footer of the site by opening themes/basic/layouts/_default/partials/footer.html, the last partial referenced in the baseof.html file. Add a footer element and a copyright date to the file with the following code:

<footer>

<small>Copyright {{now.Format "2006"}} Me.</small>

</footer>

Step 4: Use the base

To use the new base template, replace the existing layouts you’ve used with code that defines a layout “block”. In the baseof.html file, you’ll find this line:

{{- block "main" . }}{{- end }}

This line looks for a block named “main” and pulls it in. Those blocks are what you’ll define in your actual layout pages like index.html and single.html. Notice it’s also passing the current context, so you’ll be able to access it in the layout pages.

Styling the Theme with CSS

Add styling in a file: themes/basic/static/css/style.css for the site.

Then add the following to the partials head.html file:

<link rel="stylesheet" href="{{ "css/style.css" | relURL }}">

The relURL function creates site-root-relative link to the file instead of an absolute link that contains the site’s domain name. For ease of development and deployment, you should use relative URLs whenever possible. When Hugo generates the site, it’ll copy the contents of the themes/basic/static directory, including all subdirectories, into the public directory, so your CSS file will be located at /css/style.css.

In this chapter, you kept the stylesheet in the static directory of the theme instead of in the static directory in your Hugo site. It’s best to follow this convention and use your site’s static directory for images or other assets that are specific to your site, and keep things that are specific to the theme within the theme’s directory structure. When you generate your site, Hugo will grab files from both places and put them in the public directory. If you name files the same, the ones in your site’s static directory will override the ones in the theme.

Chapter 3: Adding Content Sections

Creating a Project Archetype

Shifting from using the default archetype to creating more specific archetypes for other types of content and include whatever you’d like, including placeholder content.

Create the file archetypes/projects.md and open it in your editor. Add the following to the file, which defines not only front matter, but some placeholder content:

---

title: "{{ replace .Name "-" " " | title }}"

draft: false

---

Description...

### Tech used

* item

* item

* item

Creating the List Layout

Unfortunately, if you visited http://localhost:1313/projects, instead of a list of projects, you won’t see anything at all. That’s because you haven’t defined a layout

that displays lists. Let’s do that now.

Up until this point, you’ve only worked with individual pages, like the home page or a project page. You haven’t done anything with lists of content yet. But if you’re looking to show a list of tags, categories, or in this case, projects, you have to define a layout for those named list.html.

Let’s define a default list template that will work for all list pages on the site. Open the file themes/basic/layouts/_default/list.html and add the following code to the file, which displays the title of the content page and builds a list of links to each content page:

{{ define "main" }}

<h2>{{ .Title }}</h2>

<ul>

{{ range .Pages }}

<li><a href="{{ .RelPermalink }}">{{ .Title }}</a></li>

{{ end }}

</ul>

{{ end }}

The {{ range .Pages }} section is where the magic happens. The .Pages collection contains all of the pages related to the section you’re working with. When Hugo builds the list page for Projects, for example, it collects all the pages within content/projects and makes those available in the .Pages variable in the context. The range function lets you iterate over the results so you can display each record in the collection. Inside of the range block, you access the properties of each page, as the context is now set to that specific page’s context. In this case, you’re displaying the site-relative URL and title of each page.

Creating More Specific Layouts

You’ll often find that you’ll want some pages or sections of your site to have slightly different themes or layouts. Let’s make a specific layout for project pages that displays the list of projects in the sidebar of each project page so that visitors can navigate through projects easier.

In the themes/basic/layouts folder, create a new folder named projects. You can do that on the command line like this:

mkdir themes/basic/layouts/projects/

Then, create the file themes/basic/layouts/projects/single.html. Add this code to define the main block with sections for the content and the project list:

{{ define "main" }}

<div class="project-container">

<section class="project-list">

<h2>Projects</h2>

</section>

<section class="project">

<h2>{{ .Title }}</h2>

{{ .Content }}

</section>

</div>

{{ end }}

In the project-list section, add the code to iterate over all of your projects and display a link to each page. Since you’re not working with a collection in a list layout, you won’t have access to a .Pages variable. Hugo provides a mechanism where you can access any content collection. The .Site.RegularPages variable gives you access to all of the pages in your site. You can whittle that down with the where function, which works similar to how a SQL statement works.For example, to find all of the Project pages, you’d write this statement:

{{ range (where .Site.RegularPages "Type" "in" "projects") }}

So, to display the list of all projects, add this code to the project-list section:

<section class="project-list">

<h2>Projects</h2>

<ul>

{{ range (where .Site.RegularPages "Type" "in" "projects").ByDate.Reverse }}

<li><a href="{{ .RelPermalink }}">{{ .Title }}</a></li>

{{ end }}

</ul>

</section>

You can sort the items too. If you’d like to order them by the most recent project first, use the .ByDate function and the .Reverse function like this:

range (where .Site.RegularPages "Type" "in" "projects").ByDate.Reverse

If you only wanted to display the most recent project, you could do this:

range first 1 (where .Site.RegularPages "Type" "in" "projects").ByDate.Reverse

Adding Content to List Pages

When you visit http://localhost:1313/projects,you see a list of projects and nothing else. Let’s add some content to the page as well. To add content to list pages, you need to add an _index.md file to the folder associated with the content. This is similar to how you added content to your site’s home page.

Create the file content/projects/_index.md. You can do this with the hugo command:

hugo new projects/_index.md

Then add the following into the _index.md file created:

title: “Projects” draft: false

This is a list of my projects. You can select each project to learn more about each one.

Ensure the list.html has the {{ .Content }} block so that the text is displayed.

Customizing the Project List

Just like how you can create layouts for individual items in a content section, you can control how the list for a content section looks with its own list layout. The default list layout uses a bulleted list, but let’s make a layout for projects with a little more structure.

Create the file themes/basic/layouts/projects/list.html. Define the main block, bring in the page title and the content section, and then iterate through the pages the same way you did for the default list page, but use HTML sectioning elements instead of a list:

{{ define "main" }}

<h2>{{ .Title }}</h2>

{{ .Content }}

<section class="projects">

{{ range .Pages }}

<section class="project">

<h3><a href="{{ .RelPermalink }}">{{ .Title }}</a></h3>

</section>

{{ end }}

</section>

{{ end }}

Working with Data

Using Site Configuration Data in Your Theme

Your layouts use {{ .Site.Title }} to display the name of the site in the browser title bar and in your header navigation. You can place all kinds of other data in your site’s configuration file and use it as well.

Open hugo.toml and add a new params section that defines the author of the site and a description of the site:

[params]

author = "Brian Hogan"

description = "My portfolio site"

Then, open the file themes/basic/layouts/partials/head.html and add a new author meta tag to the page:

Page 36 has information on how to configure Google Analytics.

Add more to archetypes

Extend the projects archetype as follows:

---

title: "{{ replace .Name "-" " " | title }}"

draft: false

image: //via.placeholder.com/640x150

alt_text: "{{ replace .Name "-" " " | title }} screenshot"

summary: "Summary of the {{ replace .Name "-" " " | title }} project"

tech_used:

- JavaScript

- CSS

- HTML

---

Description of the {{ replace .Name "-" " " | title }} project...

Now we can update the single.html for projects to use the additional data fields:

<section class="project">

<h2>{{ .Title }}</h2>

{{ .Content }}

<img alt="{{ .Params.alt_text }}" src="{{ .Params.image }}">

<h3>Tech used</h3>

<ul>

{{ range .Params.tech_used }}

<li>{{ . }}</li>

{{ end }}

</ul>

</section>

Notice that the image, alt_text, and tech_used fields are prefixed by .Params. Any custom fields you add to the front matter get added to this .Params collection. If you don’t add that prefix, Hugo won’t be able to find the data. Fields like description and title are predefined fields that Hugo knows about, so you don’t need the params prefix when referencing them.

You can find the list of predefined fields in Hugo’s documentation..

Conditionally Displaying Data

Using with instead of isset due it’s limitations when dealing with empty vs. default vs. set values.

To handle cases where you’re checking for a value in default variable like this, use Hugo’s with function. Replace the existing meta description in themes/basic/layouts/partials/head.html with this block of code, which conditionally

sets the description:

<meta name="description" content="

{{- with .Page.Description -}}

{{ . }}

{{- else -}}

{{ .Site.Params.description }}

{{- end -}}">

Now add the description field to the _index.md in the projects directory in the content directory.

The <title> element currently uses the title of the site and doesn’t accurately reflect the title of an individual page. This can be bad for search engine ranking, but it’s also bad from a usability standpoint. The value of the <title> tag is what appears in the browser title or bookmark tab, as well as a bookmark someone creates. Let’s use the default site title on the home page, and use the more specific page title everywhere else. To do this, use an if statement with the built-in .Site.IsHome variable to check to see if you’re on the home page or not and display the site title or the more specific page title. Modify the head partial and replace the existing <title> tag with this code:

<title>

{{- if .Page.IsHome -}}

{{ .Site.Title }}

{{- else -}}

{{ .Title }} – {{ .Site.Title }}

{{- end -}}

</title>

Notice that this code appends the site title to the page title, which is a common practice when optimizing your site for search engines, as the page title shows up as the title in search results. With these changes in place, your page’s data more accurately reflects the specific page.

Using Local Data Files

Sometimes you might want to drive sections of your site from other data sources. Let’s look at how to do that.

See page 42.

Create the file socialmedia.json in the data directory of your site:

{ "accounts" :

[

{

"name": "Twitter",

"url": "https://twitter.com/bphogan"

},

{

"name": "LinkedIn",

"url": "https://linkedin.com/in/bphogan"

}

]

}

Then in the contact.html in the _default directory in the layouts directory add:

{{ define "main" }}

<h2>{{ .Title }}</h2>

{{ .Content }}

<h3>Social Media</h3>

<ul>

{{ range .Site.Data.socialmedia.accounts }}

<li><a href="{{ .url }}">{{ .name }}</a></li>

{{ end }}

</ul>

{{ end }}

The layout you created won’t override the default single page

layout because it’s not associated with a specific type of content. When you created a layout for projects, Hugo automatically associated the layout with all content within the projects folder. In this case, there’s no association like that, so you have to explicitly assign the layout file to the contact.md Markdown file. Open content/contact.md and specify the contact layout in the page’s front

matter by adding the following code:

---

title: "Contact"

date: 2020-01-01T12:55:44-05:00

draft: false

layout: contact

---

This is my Contact page.

Pulling Data from Remote Sources

See page 44 to 48 on how data can be pulled from the GitHub API.

Syndicating Content with RSS

See page 48 to 50.

Hugo creates RSS feeds for your site automatically using a built-in RSS 2.0 template. If you visit http://localhost:1313/index.xml, you’ll find a pre-built RSS feed that includes all of your pages.

People won’t know there’s a feed for your site unless you tell them about it. To make your feed discoverable, you can add a meta tag to your site’s header that looks like this:

<link rel="alternate" type="application/rss+xml"

href="http://example.com/feed" >

Rendering Content as JSON

See page 50 to 52.

Hugo supports JSON output out of the box too, which means you can use Hugo to create a JSON API that you can consume from other applications. Unlike RSS feeds, you need to create a layout for your JSON output, and you must specify which pages of your site should use this output type.

Adding a Blog

To simplify the process of hosting your own content, you can use Hugo to add a blog to your site. To create a blog in Hugo, you’ll create a new content type, named “Post”, and you’ll create layouts to support displaying those posts.

Start by creating an archetype for a post so you have a blueprint to follow. Create the file archetypes/posts.md by copying the default archetype file:

---

title: "{{ replace .Name "-" " " | title }}"

date: {{ .Date }}

draft: false

author: ibrathesheriff

---

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit, sed do eiusmod

tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua.

Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut

aliquip ex ea commodo consequat.

Then to create your first post run:

hugo new posts/first-post.md

Then navigate to: http://localhost:1313/posts/first-post/

http://localhost:1313/posts/ will use the default list layout to display all the posts.

Creating the Post’s Layout

Create the directory themes/basic/layouts/posts/ to hold the layout. You can use your editor or use the following command in your terminal:

mkdir themes/basic/layouts/posts

Then create the file themes/basic/layouts/posts/single.html, which will hold the layout for an individual post:

{{ define "main" }}

<article class="post">

<header>

<h2>{{ .Title }}</h2>

<p>

By {{ .Params.Author }}

</p>

<p>

Posted {{ .Date.Format "January 2, 2006" }}

</p>

<p>

Reading time: {{ math.Round (div (countwords .Content) 200.0) }} minutes.

</p>

</header>

<section class="body">

{{ .Content }}

</section>

</article>

{{ end }}

This way we can tailor a post to display not only it’s content but it’s metadata.

Hugo has built-in functions for counting words and doing math, so in your template, add the following code to your byline to determine and display the reading time:

<p>

Reading time: {{ math.Round (div (countwords .Content) 200.0) }} minutes.

</p>

Organizing Content with Taxonomies

Many blogs and content systems let you place your posts in categories and apply tags to your posts. This logical grouping of content is known as a taxonomy. Hugo supports categories and tags out of the box and can generate category and tag list pages automatically. All you have to do is add categories and tags to your front matter. So open the posts archetype at archetypes/post.md and add some default categories and tags:

categories:

- Personal

- Thoughts

tags:

- software

- html

By adding the tags and categories to your post, Hugo will generate pages for those using your default list layout. Visit http://localhost:1313/tags to see the tags list.

Visit http://localhost:1313/categories/ to see the list of categories.

When you visit https://localhost:1313/tags, you’re looking at what Hugo calls “taxonomy terms.”" When you look at a specific tag, that’s what Hugo calls a “taxonomy.” This becomes important when you’d like to customise the layouts for these pages. Let’s alter the tags list so it shows the count of items associated with each tag in addition to the tag.

To customise the page that displays the list of all of your tags, create a new layout named tag.terms.html. Place it in themes/basic/layouts/_default/.

In the new file, add the usual layout boilerplate, including the title and the {{. Content }} pieces. Instead of iterating over the related pages like you have done in previous list templates, iterate over all of the tags for the site with .Data.Terms. This will give you access to the number of content pages associated with each tag:

{{ define "main" }}

<h2>{{ .Title }}</h2>

{{ .Content }}

{{ range .Data.Terms.Alphabetical }}

<p class="tag">

<a href="{{ .Page.Permalink }}">{{ .Page.Title }}</a>

<span class="count">({{ .Count }})</span>

</p>

{{ end }}

{{ end }}

You’ve included {{. Content }} in the layout. When you’re looking at the /tags section of the site, Hugo will look in content/tags/_index.md for that content. Create the _index.md file now using:

hugo new tags/_index.md

Then update the content of the _index.md file:

---

title: "Tags"

date: 2020-01-01T15:17:39-05:00

draft: false

---

These are the site's tags:

When you select a tag, Hugo looks for a layout associated with tags. If you want to customize this layout, create a layout named tags.html in the theme/basic/layouts/_default folder and use the same logic you use in your existing

list layout to pull in the content.

Now let’s add tags to posts by adding this to the themes/basic/layouts/posts/single.html:

<span class="tags">

in

{{ range .Params.tags }}

<a class="tag" href="/tags/{{ . | urlize }}">{{ . }}</a>

{{ end }}

</span>

The tags listing page is located at /tags, and each tag itself is located at /tags/tagname. As you iterate over each tag, you can construct the link to each tag by appending the tag name to /tags/. However, since tags might contain spaces or other characters, use the urlize function to encode the tag as a URL-safe string.

Hugo Support for Syntax Highlighting of Code

If you’re publishing posts, you might want to include snippets of code from time to time. Hugo supports syntax highlighting using a library named Chroma,a which is compatible with the popular Pygments syntax highlighter.

To configure this, tell Hugo you want it to use Pygments-style classes when it highlights your code. Add this line to hugo.toml:

pygmentsUseClasses = true

Then, generate a stylesheet to highlight your code using one of the available Chroma styles:

hugo gen chromastyles --style=github > syntax.css

Note: See Chroma Style Gallery for a preview of the available styles.

Then add the syntax.css style to your head.html partial.

Then add a code fragment to the post:

let x = 25;

let y = 30;

Customizing the URL for Posts

By default, your blog contents show up under posts/. For example, your first blog post is available at http://localhost:1313/posts/first-post. Many blogs use the year/month/title format for their blog post URLs. This meaningful URL shows anyone looking at the URL how old the post might be, but it also shows that the content is organized by date. In sites with content organized like this, a visitor could see content for the rest of the month, or for the whole year, by specifying the year or month.

A permalink is a permanent link to a specific page, often used when sharing a page with others through social media, newsletters, or even search results. You can use front matter on a post to control the permalink for a post by using the url field, but that’s really only meant to handle situations where you’re migrating content or need to do some one-off customization. Hugo lets you define how you’d like to structure your links in its configuration file.

In hugo.toml, add a new Permalinks section and define a new rule that makes posts available under /posts/year/month/slug:

[permalinks]

posts = "posts/:year/:month/:slug/"

This gives you URLs like /posts/2020/01/first_post. The slug is the end part of the URL that identifies the page’s content. It’s generated from the page title by default, but you can define your own slug by adding a slug field to your page’s front matter section.

If you visit /posts/2020, you might expect to find a list of all posts for that year.

Unfortunately, Hugo doesn’t support generating these pages currently, at least not without a little extra work. However, one of Hugo’s maintainers offered a practical workaround. By using Hugo’s taxonomy feature and a little clever use of front matter, you can generate archive pages of posts for years and months. You’re going to add “year” and “month” as new taxonomies, and “tag” your posts with a year and month. Hugo can then build the year and month pages for you just like it builds pages for categories and tags.

For more check out page 64.

Customizing Blog List Pages

The list of posts isn’t very appealing since we’re using the default list layout. Let’s make a layout for posts that shows the title, post date, and a summary of each post’s content.

See page 65 to 67.

Adding Pagination

As you get more content, your list page might become quite long. You can break things up with pagination.

You will use {{ range .Paginator.Pages }} see page 68 to 71.

Handling Lots of Posts

Once you’ve been adding new content to your site consistently, or if you’ve migrated content into your site, you’ll end up with hundreds of files in your ‘posts’ folder, which can be difficult to manage.

Hugo uses the folders that you create inside of your ‘content’ folder to define content sections, but you can create subfolders within these folders to organize your content in a way that works better for you. For example, you can create a ‘2020’ folder inside ‘posts’ and move all of the posts from 2020 into that folder. Hugo will still see them as posts.

By default, Hugo tries to mirror what’s on disk with how the URLs are constructed, but you can override that with the ‘url’ front matter field on each document or with the ‘permalinks’ configuration settings like you did in xxx.

You can explore content sections in more detail, including how to create nested content sections, in Hugo’s documentation.

Adding Comments to Posts Using Disqus

See page 71 to 75.

Displaying Related Content

When people find a page on your site through a social media share or a search result, you might want to make some of your other content visible as well. Hugo lets you display related content and has some sensible defaults for doing so. To enable this feature, you have to add some keywords to your pages’ front matter section.

First, open content/projects/jabberwocky.md and add the keywords section. Like tags, it’s a list:

keywords:

- jabberwocky

Add the same keywords section to content/posts/first-post.md.

Then, open themes/basic/layouts/posts/single.html and add this code below your post but above the comments section:

<section class="related">

{{ $related := .Site.RegularPages.Related . | first 5 }}

{{ with $related }}

<h3>Related pages</h3>

<ul>

{{ range . }}

<li><a href="{{ .RelPermalink }}">{{ .Title }}</a></li>

{{ end }}

</ul>

{{ end }}

</section>

This code uses a with block to check if there’s any related content. If there is, it displays the header and the list of content.

By adding the same keyword to the Jabberwocky project and the “second post” blog post, the Jabberwocky project now shows up as a related piece of content.

You can further configure this system in the hugo.toml file:

[related]

threshold = 80.0

includeNewer = false

toLower = false

[[related.indices]]

name = "keywords"

weight = 100.0

[[related.indices]]

name = "date"

weight = 10.0